24 June 2020

European coal in structural decline

Author: Felix Reitz, Energy Analyst at Europe Beyond Coal

The economic shutdown due to the COVID-19 crisis led to steep reductions in CO2 emissions from the power sector. While this development was of exceptional nature, it is important to highlight that CO2 emissions from European coal power stations were already in structural decline before the pandemic. To achieve a more sustainable future, the trend must continue as economies are revived.

In these extraordinary times, 2019 may feel like a long passed era. The COVID-19 pandemic has had tremendous impacts on all aspects of society, the energy industry included. In Europe, power demand reductions led to less coal use, but newly published data by the European Commission (EC) shows that this drop has not come out of the blue. In the European Union, coal was in structural decline already, and the process accelerated in 2019. This has significant implications for countries like Germany which is finalising its coal phase out, and Poland, which is making noises about a phase out in the 2040’s, but neither reflect the accelerating decline of coal.

Big declines for lignite and hard coal

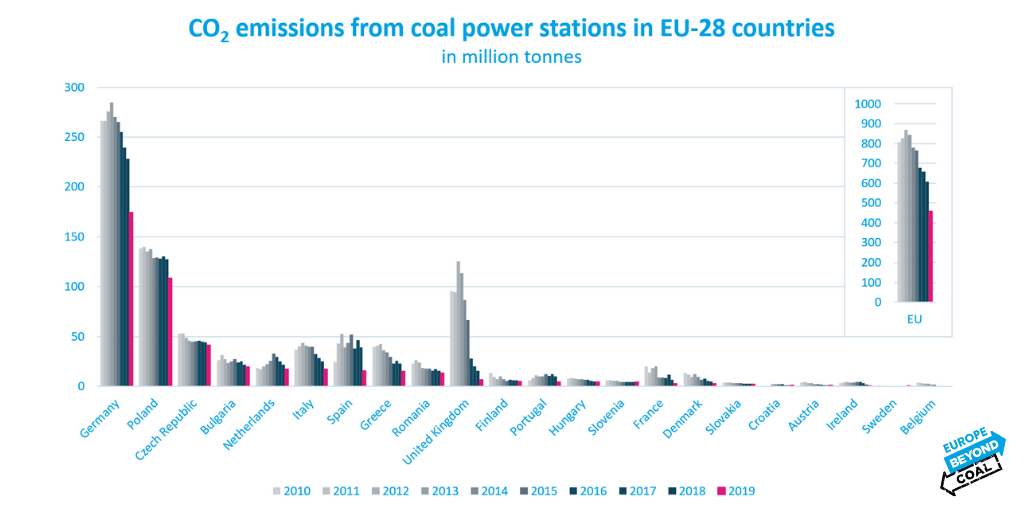

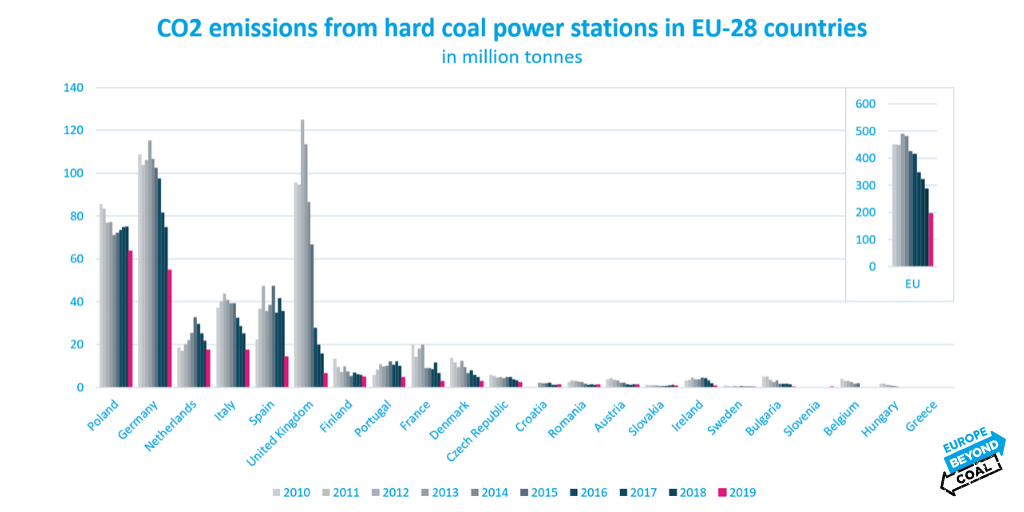

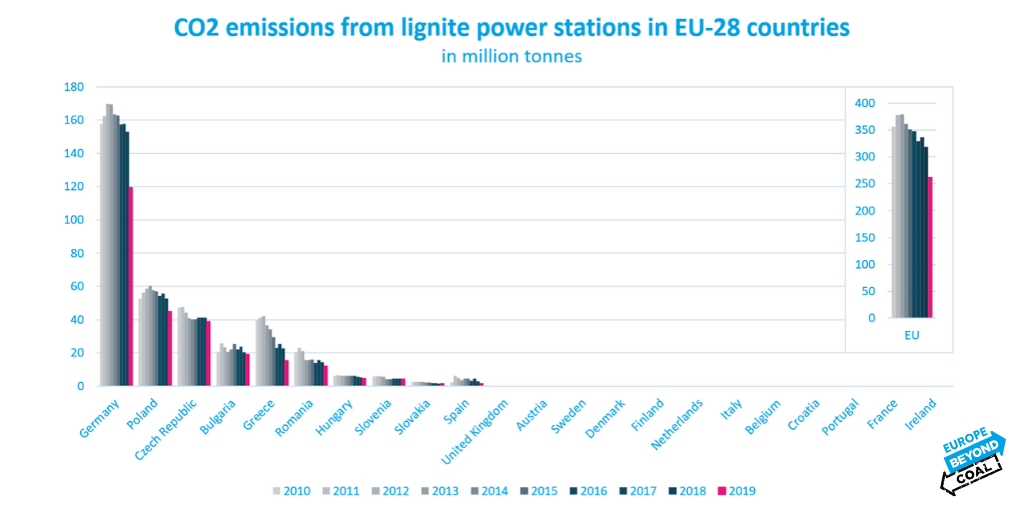

The most recent data from the EU Transaction Log, the Union’s registry of the emissions trading scheme (ETS), shows a steep reduction of CO2 from coal power stations across the continent in 2019. In total, emissions dropped by approximately 147 million tonnes, which is a reduction of 24.5 percent year on year. Lignite dropped by 18 percent, hard coal by even 32 percent. The strongest absolute decline happened in Germany, with 54 million tonnes of CO2 less than the previous period. Extraordinary drops have also been recorded in Spain, where coal emissions dropped by 23 million tonnes, and In the United Kingdom which saw more than nine million tonnes eliminated.

The new low is the result of an accelerated decline that started in 2012, when the EU’s CO2 emissions from coal power stations peaked. Since then, coal-based CO2 emissions have dropped by 47 percent. In other words: they nearly halved in less than a decade. Reductions of hard coal were even stronger (-60 percent), with about one third of the decline happening in 2019 (-92 million tonnes). The decline in CO2 emissions from lignite was less distinct (-31 percent). Half of this decline happened in 2019 (-56 million tonnes).

The drop in emissions from lignite power stations was mostly due to changes in Germany, Poland and Greece. Emissions from lignite in other countries remained relatively stable (note: the data availability for 2019 emissions in Bulgaria is limited and was filled with 2018, which automatically led to almost constant emissions).

Europe’s Dirty-30 updated: Germany and Poland dominate

The ranking of Europe’s 30 most CO2 emitting coal plants shows only few changes. Power stations in Germany and Poland are still dominant, taking the top nine places.

Stronger policies, but too much coal replaced with gas

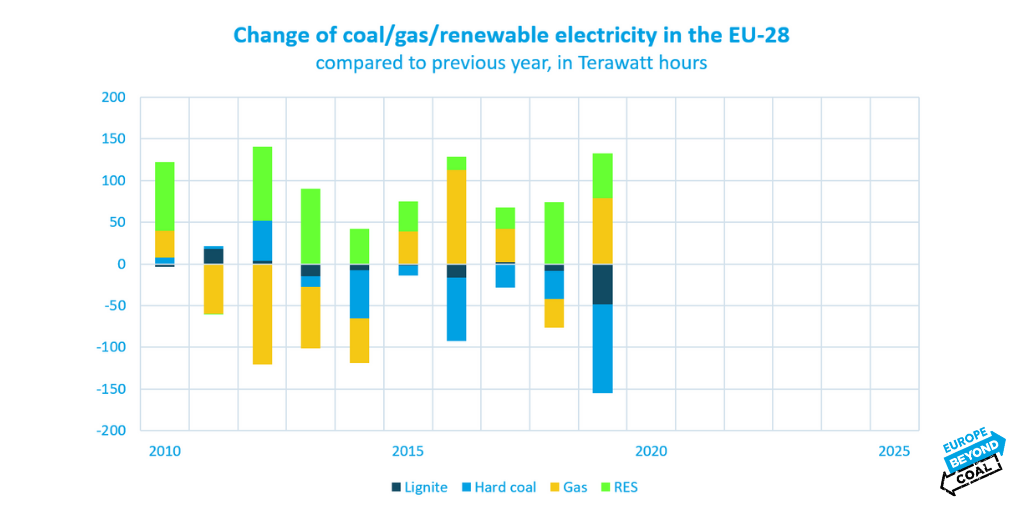

Coal’s decline is closely linked to its deteriorating economics. While renewable energies are being expanded and producing at ever higher levels with consistently decreasing cost, an effective carbon pricing regime, tightening pollution limits for large combustion plants and changed fuel prices means that coal in the power sector gets crowded out on two sides: gas and renewables.

Unfortunately, the absolute growth of gas was higher than the growth of renewables in 2019. Roughly 40 percent of coal power was replaced by renewables, 60 percent by gas. Most of the increase of gas generation was due to higher competitiveness of existing plants, rather than capacity additions.

There are very few new gas power plants being built in Europe, however, there are worrying signs that politicians may turn to support new fossil gas power plants instead of investing in renewable technologies. An example is a recent push by EU member states from Eastern and South Eastern Europe that would like to see an important role of gas in the EU and corresponding regulation. However, there is a growing risk that such unsustainable investments become stranded assets just like the coal plants that were erected in the last decade.

Meanwhile, wind and solar deployment rates need to triple or more for the EU to decarbonise fast enough. This means that decision makers should give strict priority to renewable energy and as part of any ‘green recovery’ exclusively focus on non-fossil options.

Source: Agora Energiewende/Sandbag (2020): The European Power Sector in 2019: https://ember-climate.org/project/power-2019/

A 2030 coal phase-out is needed

The most important implications for the current crisis response are long-term. The task of rebuilding Europe’s economies should include governments strengthening the role of renewable energy and energy efficiency, while ensuring coal regions are given strong support to transition to new and sustainable economic structures. This combination requires strong regulatory signals and political support to create investments in this new energy structure. A European coal phase-out by 2030 is an integral part of this transition.

One of the frontrunners in this respect is the United Kingdom, whose power system has been coal-free for more than two months at this point. Just eight years ago its coal-based CO2 emissions were nearly as high as those from Poland at the time. Now the coal phase-out will come well ahead of 2025, which initially was intended to mark the end of coal power in the United Kingdom.

Unfortunately, other coal-heavy countries that need to be taking a similar line to the UK, such as Germany and Poland, are picking phase out dates that don’t reflect the reality of the coal crash, or respect the implications of the Paris agreement. This leaves communities unnecessarily exposed to yet more health and social impacts of coal in the short term, and workers facing greater risks of a hard landing in the future when the end of coal comes sooner than planned for.

At the same time it is important to not forget about the threat of new coal projects. Despite all, there is still a long list of planned coal power stations in Europe, most of them located in the Western Balkans and in Turkey. The respective governments should distance themselves from these projects as a means to revive their economies and instead endorse sustainable alternatives that contribute to clean air and public health.

Now is the time to break new ground and focus on measures that respond to both crises effectively: pandemic recovery and climate change.