09 March 2020

EPH gambles against market and climate with acquisition of 900 MW Schkopau coal power plant

by Joshua Archer, Coal Finance and Utility Coordinator, Europe Beyond Coal

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On February 21, Czech-based energy investor Energetický a průmyslový holding, a.s. (EPH), announced its intent to acquire the remaining shares of a 900 MW coal power plant in the German city of Schkopau, through its subsidiary Saale Energie, which currently owns 42 percent of the Schkopau project.

The acquisition shows how EPH is fast becoming a textbook example of how certain bad-faith players in the energy sector are positioning themselves and their stakeholders for big losses as coal’s economic case continues to evaporate.

Schkopau acquisition is latest in EPH’s aggressive coal expansion strategy

Today, EPH is Europe’s second-largest coal power plant operator and third-largest emitter of carbon from coal. It has achieved this precarious position despite coal’s flailing prospects in the context of greater urgency for climate action and growing evidence of the severe public health impacts of coal emissions.

|

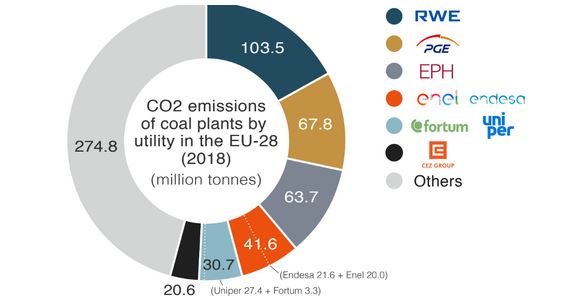

In 2018, EPH coal plants emitted 63.7 million tonnes of carbon, positioning the company for a close third-place behind Polish PGE for coal-based carbon emissions. Source: Fool’s Gold |

While there may be some dubious euros to be made in coal closure compensation rackets, as demonstrated by a recent scandal involving EPH subsidiary LEAG, EPH’s coal strategy is at odds with every other warning light flashing in its face. Not only are trends in the broader investment community moving away from coal assets, including a recent commitment from the world’s largest asset management firm, BlackRock, but renewable energy solutions are also increasingly eating coal’s breakfast, lunch, and dinner while EU policy changes weigh heavier and heavier on coal’s economic case.

EPH’s coal exposure creates substantial risks to investors amid growing momentum toward a 2030 coal phase-out across Europe. According to Urgewald’s Global Coal Exit List, coal comprises a 50-percent share of EPH’s generating capacity, with an installed coal capacity of 12.2 GW.

EPH’s coal shopping spree continued in 2019

Last year, coal made up nearly half of the generating capacity newly added to EPH’s books. In fact, 94 percent of the 4,000 MW of the EPH capacity added in 2019 is fossil fuel-based, including 1,800 MW in new coal.

In June 2019, EPH bought the 565 MW Kilroot coal and oil-fired power plant from AES, in Northern Ireland, along with a 708 MW gas-fired power plant. In the summer, the French market authority approved EPH’s acquisition of more than 2 GW from German utility company Uniper, which includes two coal-fired power plants—Provence (625 MW) and Emile-Huchet (647 MW). That purchase also included two gas-fired plants (828 MW); 150 MW of biomass, and 100 MW of wind and solar power generation., And finally, in October 2019, EPH completed the purchase of a 400 MW gas-fired power plant in Galway, Ireland. EPH is rapidly turning into the unscrupulous buyer of outdated coal assets which should be closed, not sold, by utilities seeking to clean up their portfolios and images.

Schkopau case demonstrates need for a “close-not-sell” code of conduct in financial services

Closing a working asset rather than selling it may sound counterintuitive from a business point of view. That said, as Europe Beyond Coal’s latest briefing makes clear, given that the point of taking responsibility for phasing out coal is to reduce emissions, selling a plant merely makes it someone else’s—and by default everybody’s—problem. In this context, Schkopau is yet another disappointing setback in efforts to combat the worsening consequences of climate change.

In a press release, Uniper—EPH’s accomplice in this climate crime—portrayed the Schkopau sell-off as a “milestone in the decarbonisation of the Uniper portfolio.” By characterising the deal in this way, Uniper is attempting to get away with egregious greenwashing. In truth, the company has done nothing to decarbonise Europe. It has merely dumped its garbage into someone else’s bin.

The deal is particularly cringe-worthy for the Finnish state-owned power utility Fortum, the soon-to-be majority owner of Uniper. While pursuing its self-proclaimed For a cleaner world business strategy, Fortum seems perfectly content to see plants’ operational lives extended through sell-offs. This framing also reflects a key challenge in the move toward more climate-conscious investment.

The Schkopau deal also suggests EPH is making a business of extending the operational lifecycles of the dirtiest plants in Europe, even as the global community is clamoring to end the climate crisis. Indeed, Schkopau resembles the 2016 EPH acquisition of German mines and plants then owned by Swedish utility Vattenfall. In short, EPH is attempting to make a profit by subverting all the good work of investors and civil society to persuade standard utilities to end coal-fired power generation.

EPH must adopt a meaningful climate policy immediately

EPH has gained infamy for buying up the oldest, most polluting coal assets across Europe, and keeping them running at great cost to human health, national budgets, and our global climate. The company’s lack of any meaningful policy on climate or carbon risk should be a cause for investor concern and public anger.

Financial institutions should also be cautious of potential corporate governance issues associated with backing EPH. While its polluting infamy grew, EPH has shuffled its ownership structure. While most of EPH is owned by Czech multi-billionaire Daniel Křetínský, EPH’s latest annual report shows the company’s formal ownership is distributed between two Luxembourg-based companies: E.P. Investment S.á.r.l., and E.P. Investment II S.á.r.ll. If its coal gambles were not cause enough for investor wariness, reasonable questions could surface about governance and risk management at any financial institution willing to fund business operated through such a murky organizational structure.

As an unlisted private equity firm, EPH also operates without oversight from wider general assemblies. Whereas investors have held other energy companies to account on climate action, financial institutions backing EPH have limited sway on key management decisions because the company is majority-owned by one wealthy individual. Finally, because EPH has very few retail customers, the company is not sensitive to customer pressure on climate.

This makes EPH a slippery character, though it does face its own challenges: access to critical loans could be limited if it fails to adopt policies to address its role in the climate crisis. An increasing number of banks are tightening lending conditions to rule out coal, and at least ten banks have committed to cut ties with companies with exposure to coal over 50 percent. Some banks have adopted even tighter exposure thresholds for client companies.

As the above demonstrates, EPH is playing a high-risk game, and it will not be able to hide the stakes of its gamble for much longer. The dice will inevitably fall against it.